Spotted Migrants of the Forest Floor

By Robert Windham

While staff at the Tennessee River Gorge Trust wait for the arrival of neotropical migratory birds in spring, did you know there is evidence of an entirely separate terrestrial migration happening this winter right at our feet? Specifically, the breeding migrations of spotted salamanders (Ambystoma maculatum) is in full swing!

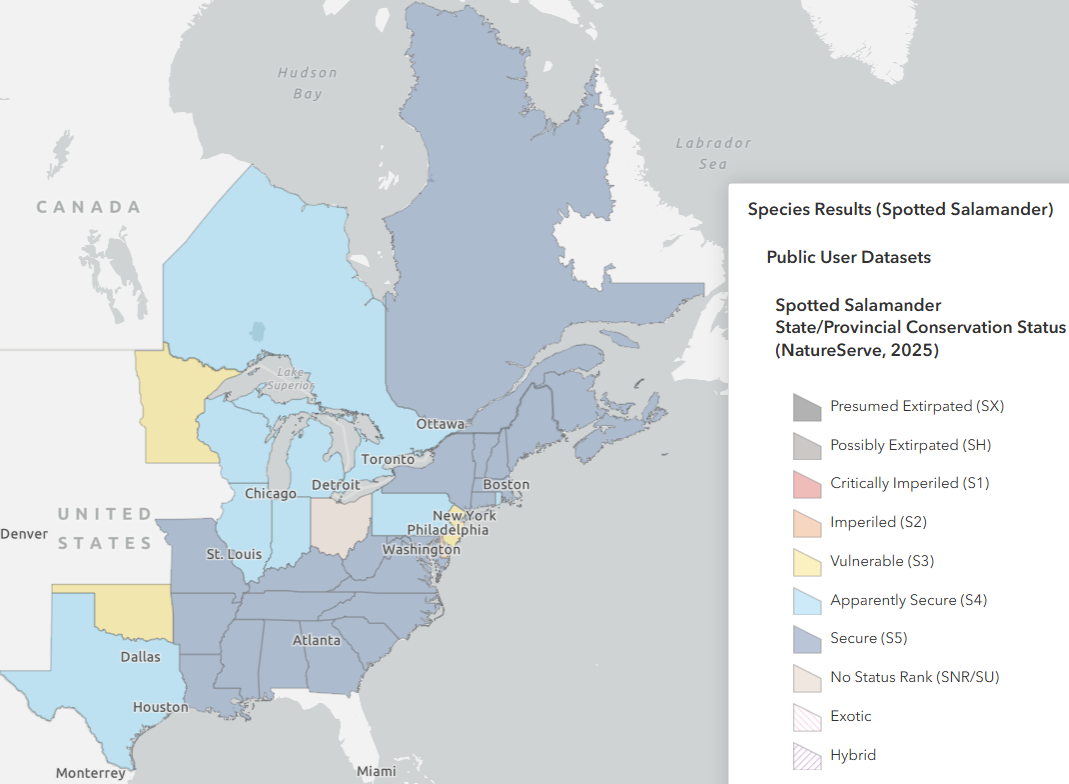

Spotted salamanders are found across much of the eastern United States and Canada in hardwood and mixed mesic forests near available aquatic breeding sites like seasonal, fishless wetlands. Photo Credit: NatureServe.org

Like other terrestrial mole salamanders, spotted salamanders spend most of their juvenile and adult life in underground burrow systems or under moist cover objects. Data compiled from the Virginia Herpetological Society show that some burrow systems of individual adults exceed over 130 square feet of the forest floor! When environmental conditions are just right, spotted salamanders emerge from their subterranean overwintering refuge and migrate over 600 feet toaquatic breeding sites.

The timing of this migration entirely depends on precipitation and temperature cues and thus varies greatly throughout their range, with migration occurring as early as December in the south and as late as April in the north. The trigger for this migration occurs on rainy nights of the following days once soil temperatures at a depth of 12 inches surpass 40°F.” Sexton et al. found that 98% of all migration occurred when there was at least one tenth of an inch of rainfall and an average 3-day temperature of 42°F for a spotted salamander population studied in Missouri over 10 years. Often referred to as a “Big Night,” mass spotted salamander migrations can involve up to 100 individuals visiting a single breeding pool overnight. Volunteers of the Salamander Crossing Brigade with the Harris Center for Conservation Education in New Hampshire provided safe passage for 1,066 spotted salamanders at 35 different road crossing sites for the 2024 spring season. These volunteers counted 59 spotted salamanders crossing the road in just one night!

Example of a cloudy white egg mass and spermatophores in a Tennessee River Gorge vernal pool. Photo Credit: Rob Richie (TRGT volunteer herpetologist).

For more northerly populations, the breeding season can be restricted to a few days with the right conditions. Here in the south, spotted salamanders can have up to 3 major bouts of breeding migration over the course of 2 months. Once at the breeding pool, males use submerged vegetation to deposit spermatophores that are eventually picked up by females. Females will often gather multiple spermatophores making multiple paternity common in these salamanders. Females can deposit multiple egg masses, each containing upwards of 100 eggs. Egg masses are either clear, milky white, or green. A milky white coloration occurs when females deposit a protein in the outer layer of the egg mass while a green coloration comes from a much more unexpected culprit.

Green egg masses are an example of mutualistic endosymbiosis. Endosymbiosis is a relationship where one organism lives within the cells of another organism. A well-known example of this relationship can be seen between single celled algae, zooxanthellae, living inside the cells of reef building coral. The algae supply nutrients to the coral, aiding their growth and reproduction, while the coral provides algae with both a protected environment and the carbon dioxide and water needed for photosynthesis. For spotted salamander eggs, Chlorococcum amblystomatis, previously Oophila amblysomatis, is a single-celled green algae that invades and grows inside salamander host tissues and cells, eventually disappearing during the final larval stages of development. As explained in Kerney’s research, the algae support salamander embryo growth and hatchling survival by increasing available oxygen while the salamander’s embryo’s waste supports algae population growth. Spotted salamander clutches raised with the presence of this algae have decreased embryonic mortality and reach a later developmental stage at hatching.

A collection of spotted salamanders found during a “Big Night” survey to determine breeding usage of a protected wetland. Photo Credit: Rob Richie (TRGT volunteer herpetologist)

Throughout the Tennessee River Gorge, we already have evidence of spotted salamander breeding activity in the scattered vernal pools on our landscape. As obligate users of seasonally available ponds like vernal pools, spotted salamanders rely on these habitat types for breeding and reproduction. Because of their seasonality, vernal pools are devoid of fish, thus protecting salamander eggs from predation. Other obligate users of vernal pools in our region include wood frogs, marbled salamanders, and eastern fairy shrimp. While the presence of vernal pools is influenced by soil type, underlying geology, and local hydrology, they are commonly found across the Cumberland Plateau and throughout north facing forested slopes of the Tennessee River Gorge. If you come across a vernal pool while exploring our region, the best course of action is to leave it undisturbed because you never know what critters might be using it. Take time to enjoy some herping (biologist slang for searching for amphibians) this winter and spring, and if the conditions are right, you might just encounter a party of spotted salamanders marching to their breeding grounds!

If you’re interested in learning more about vernal pools and their importance to spotted salamanders, check out this Riverwatch blog from our partners at the Tennessee Aquarium. And, if you’d like to see videos of a breeding pool full of spotted salamanders, check out this blog by Lang Elliott.