Recap of 2024 Bird Banding Season

By Austin Young

Measuring Bird Use of the Tennessee River Gorge

For decades, TRGT staff and volunteers have employed mist netting surveys in the Tennessee River Gorge, hereafter Gorge, in order to measure bird species diversity, community composition, and bird behavior at specific sites of interest on TRGT protected conservation lands. Those terms are scientific language for what birds are here, how many are there, and what does their behavior tell us about how they are using a particular area. Are they using the area to nest? To replace feathers between when they nest and spend the winter? Or to briefly stop and rest and restore fat reserves during migration? Are these birds able to get the food they need from this site?

Catching and banding birds allows researchers to answer these specific questions and get other specific data about birds that they could otherwise not obtain without having the bird in the hand. Furthermore, using mist nets and banding birds allows researchers to “follow” individual birds that use the same area consistently. Using mist nets also increases the likelihood that researchers will capture species that are secretive and hard to find. In other words, mist netting can sometimes be the only way to see what secretive species are using a site. Researchers communicate their mist netting survey results with land managers, who then use the information to guide the management of the habitat.

Bird banding not only provides high quality information about how birds use a site but uniquely provides opportunity for visitors to observe wildlife at close range and observe birds in ways most people have never experienced. Thank you to all who visited our bird banding station this year. If you haven’t already, please subscribe to our newsletter so you can get a heads up on our public bird banding days in 2025!

It’s great to band birds and all, but what do we do with the information we get from mist netting surveys?

Knowing what birds are in an area and what they are doing informs us about the state of the protected lands that TRGT is in charge of stewarding. We then use what we learned to guide what we should do to maintain or increase the land’s “ecological health” so-to-speak. In other words, how the birds are using the site give us an insight into the ability of a location to sustain healthy, flourishing bird populations. We use the mist netting survey data to guide our management actions and goals.

Close-up photo of a bird’s wing, specifically a Tennessee Warbler. Looking closely at features of a bird in the hand provides incredibly specific data, such as feather condition, for example and provides information that a researcher could not measure without having the bird in the hand.

TRGT is not alone in using this method. Using mist nets and bird banding to measure bird use of an area is a well-established method of information gathering that informs land and wildlife managers both about the birds themselves and the vegetation and insects that these birds use in order to survive and reproduce. Recapturing specific individual birds is a great example of one way that we get this information. We often recapture the same individuals over time and by recording the same data over and over again on the same birds, we can document if that bird’s physical state or behavior changes or remains the same over time or as we undergo habitat restoration efforts. In this way, mist netting provides high quality information about how those birds are using the site as we intentionally restore the habitat.

Summary of the 2024 Mist Netting/Bird Banding Effort

In 2024, TRGT staff and volunteers mist netted during autumn and spring migration at our Bird Observatory research site and did a couple of late summer surveys in between the spring and autumn migration periods in order to measure what locally breeding birds were doing before migration. Before going further, let’s briefly mention the habitat and context of the research site. The Bird Observatory site sits along the Tennessee River in the bottom of the gorge. It’s a closed-canopy forest (wherein little sunlight reaches the forest floor). The primary vegetative components are oak-hickory woodlands with mature white oak and shortleaf pine stands. Beech trees and maples are mixed in as well with patches of Chinese privet and other woody shrub species. In this habitat type, we captured primarily birds that use woodlands and shrubs, as opposed to other groups of birds that use grasslands, marshes, or other habitat types.

An adult male Scarlet Tanager replacing its breeding season feathers (red) with its winter season feathers (green). Replacing feathers is known as molting. Molting is necessary for birds because they need to replace old and worn out feathers with new, fresh feathers!

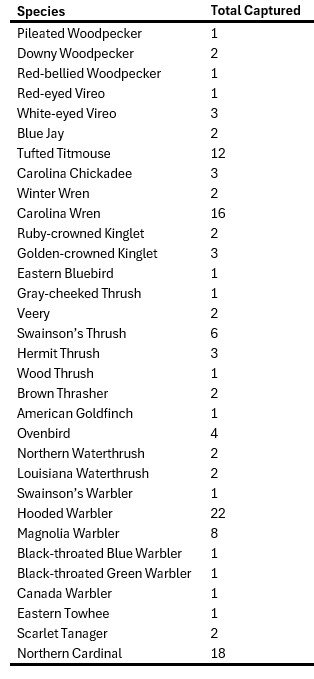

In total, we captured 128 unique individuals comprising 32 species at the Bird Lab site in 2024 (See Table 1 below). We mostly captured Hooded Warblers, Carolina Wrens, Tufted Titmouse, and Northern Cardinals. Most of the Hooded Warblers were early in autumn migration or just before migration was in full swing. Therefore, most of the Hooded Warblers were likely individuals that nested in the area or were born in the area and were preparing for migration. We also captured two Scarlet Tanagers, one of which was an adult male replacing its feathers before autumn migration southward.

The other three species we caught most of (Carolina Wren, Tufted Titmouse, and Northern Cardinal) are considered resident species. Meaning, they tend to stick around in the same area for most of their lives. We often captured these resident birds in pairs or singles throughout the year. We often caught young of the year during late spring and early autumn! During migration periods, we also captured a small number of migratory warbler species that were a fun addition to the daily totals! Further, capturing these species showed that the Bird Observatory serves as a stopover site for birds that do not nest here or spend the winter here.

An adult female Northern Cardinal facing head-on! Their massive beaks are unique among birds in southeastern Tennessee, with only two other species showing similarly sized beaks (the Blue Grosbeak and Rose-breasted Grosbeak).

The same Northern Cardinal as pictured on the left, but with a side-profile. Birds with crests, like Cardinals, are fun to watch because you can discern much of their behavior based on the position of their crest!

Magnolia Warbler! A common migrant during autumn migration that uses the Bird Lab to rest and restore fat reserves before continuing on with migration.

Unfortunately, we were unable to mist net during the second half of September as a function of the tropical storm weather that affected much of the southeastern United States. If we had been able to, it is likely we would have captured more thrushes (i.e., Gray-cheeked, Veery, and Swainson’s) and more warbler species. As expected, we captured very few sparrows and no flycatcher species (e.g. phoebes, kingbirds, pewee, flycatchers). This speaks to the closed-canopy forest habitat since sparrows and flycatchers usually prefer open habitats on the edges of woodlands. We did, however, capture one Eastern Towhee! Indicating that it’s possible birds preferring open-canopy habitats likely use the site but in small numbers.

During migration periods, we also captured a small number of migratory warbler species that were a fun addition to the daily totals! Further, capturing these species showed that the Bird Observatory serves as a stopover site for birds that do not nest here or spend the winter here. One of these species was a locally rare Swainson’s Warbler!

Swainson’s Warbler! A locally rare and very secretive species during migration that has a very restricted range in the southeastern United States. The fact that Swainson’s Warblers are possibly using the Tennessee River Gorge as a fall migration stopover site is excellent news that serves to show the importance of the Gorge to species we often see and to species are very rarely encounter.

Black-throated Blue Warbler! An uncommon migrant during autumn migration that tends to migrate through a little later in autumn than other warbler species.

Unfortunately, we were unable to mist net during the second half of September as a function of the tropical storm weather that affected much of the southeastern United States. If we had been able to, it is likely we would have captured more thrushes (i.e., Gray-cheeked, Veery, and Swainson’s) and more warbler species. As expected, we captured very few sparrows and no flycatcher species (e.g., phoebes, kingbirds, pewee, flycatchers). This speaks to the closed-canopy forest habitat since sparrows and flycatchers usually prefer open habitats on the edges of woodlands. We did, however, capture one Eastern Towhee! Indicating that it is possible birds preferring open-canopy habitats still use the site in small numbers.

A pair of Golden-crowned Kinglets in the hand are worth more than two in the bush! This species is not often captured and these birds were in different nets but on the same day in mid-October. The left bird is a male (note the orange in the crown) and the right bird is a female. Photo Credit: Eliot Berz.

Summary Table of the 2024 Mist Netting Survey Season

Table 1. A list of species and the total number captured during mist netting surveys in 2024 at the TRGT Bird Lab Site. Highlights include a Swainson’s Warbler and a pair of Scarlet Tanagers! The tanagers were an adult male and a juvenile caught together in the same net on the same day.