By Robert Windham

Periodical Cicada. Photo Credit: Austin Young.

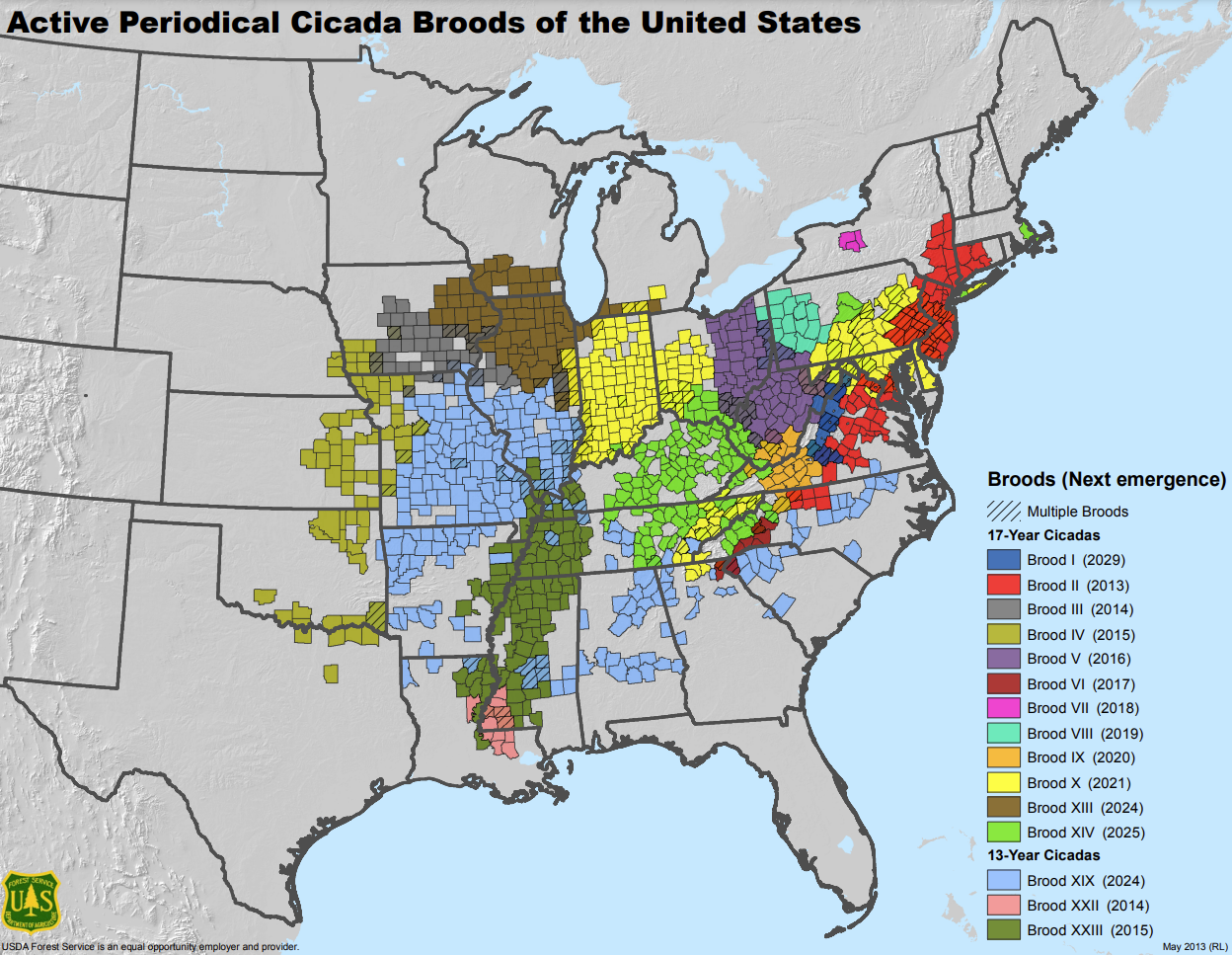

If you’ve ever experienced a summer in the southeast, you’ve likely heard the distinctive buzz of a male Cicada attempting to attract a mate. Halfway through the spring of 2024, this buzz amplified 10-fold after the Tennessee River Gorge welcomed millions of periodical Cicadas ready to complete their last month of life. Although our region experiences annual cicadas marked by their black eyes and green body parts, the periodical Brood XIX emerged in Hamilton County for the first time since 2011. Brood XIX is 1 of 3 Cicada broods in the Eastern United States that experience a 13-year life cycle, and they are distinguished from annual Cicadas by their orange wings and red eyes.

Map of active periodical Cicada broods. Photo Credit: USDA Forest Service.

Annual Cicada.

Photo Credit: Timothy Reichard

Periodical Cicada.

Photo Credit: Austin Young

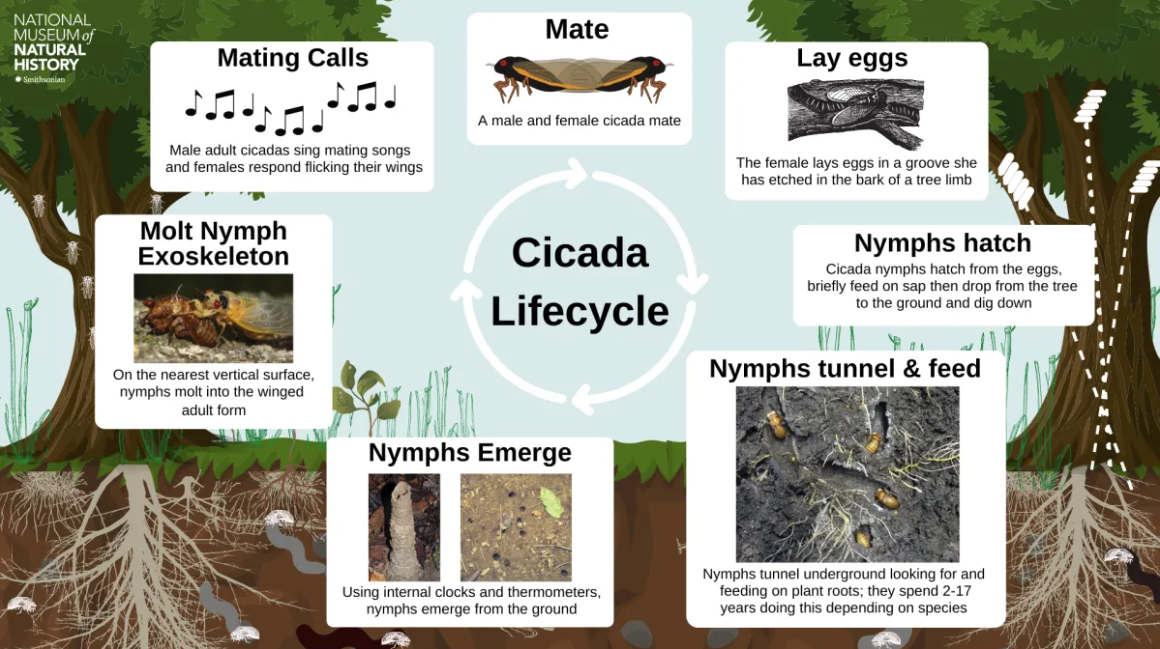

Cicada emergence holes on Williams Island, Chattanooga, TN.

Most of the 13-year life cycle for these periodical Cicadas is spent underground in development as they drink the sap from the roots of trees. Once the soil temperature reaches at least 65°F and there is adequate rainfall to soften the ground in a designated brood’s year, Cicada nymphs exit the surface through constructed tunnels to eventually shed their exoskeleton and emerge as adults. After emerging, male Cicadas use vibrating abdominal membranes called tymbals to create their distinguished buzzing noise in search for a female mate. The buzz from multiple Cicadas at once can exceed 100 decibels, louder than a gas-powered lawnmower. Adult Cicadas die around a month after emerging, and females can lay hundreds of eggs before their departure. Cicada nymphs hatch from their eggs after 1-3 months to make their journey back into the ground for 13 long years.

Cicada exoskeleton on Aetna Mountain, Chattanooga, TN.

While the lifespan of periodical broods above ground is relatively short, their sheer numbers create a resource pulse with significant environmental impacts both on land and in water. With certain areas experiencing more than 1 million Cicadas per acre, this influx provides an extra feeding opportunity for insect eating species like the American Robin, Wood Thrush, Raccoon, Bass, Eastern Copperhead, and even Orb-weaver spiders. Using data from 37 years of North American Breeding Bird Surveys, Walter Koenig and Andrew Liebhold found a distinctive ebb and flow pattern to bird populations in association with periodical Cicada emergences in the eastern United States in their 2005 study: https://wkoenig.cornell.media3.us/K127TA_05.pdf.

Species such as Gray Catbird and Brown Thrasher substantially increased following emergence years before their populations stabilized. Others like the Yellow-billed Cuckoo were recorded in high numbers during emergence years and ultimately declined in abundance over subsequent years.

Periodical Cicadas not only impact our insect predators, but they also play a key role in nutrient cycling. Emergence holes alter the water infiltration and microbial activity of the soil. After tunneling through the surface, Cicadas uproot below ground nutrients like nitrogen and deposit those to shallow rooted plants once their carcasses decompose on the forest floor. Years following, forest growth can increase as a result. Cicadas also provide a similar nutrient transfer in aquatic environments where emergence years can be indirectly linked to the status of aquatic predators.

Cicada Lifecycle. Photo Credit: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

The influence on demographics and nutrient cycling from periodical Cicada broods highlight their ecological importance both in the short and long term. At TRGT, understanding the role Cicadas play in our environment helps our interpretation of long-term ecological trends, especially in relation to the conservation and management of some of our most common imperiled bird species. We hope you all enjoyed 2024’s Cicada frenzy or are enjoying the newfound silence across our landscape now that most of Brood XIX is underground until their eventual return in 2037.

To learn more about our periodical Cicadas, visit the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History website: https://naturalhistory.si.edu/education/teaching-resources/life-science/periodical-cicadas

Cicadas buzzing at Williams Island, Chattanooga, TN.