Wood Thrush Motus Tracking Research

Introduction and Scientific Background

Birds are unique animals, the only ones with feathers, that occupy irreplaceable roles in ecosystems around the world. If all birds were to plummet to extinction, their respective ecological niches would suffer, producing many negative consequences. But more than that, people would simply miss birds on the landscape. We have a reverence for birds and perhaps most so for migratory birds that seem to join resident species, like Northern Cardinals and Carolina Wrens, in bringing Tennessee woodlands to life each spring with their beautiful songs and colorful plumages. In the field of science and wildlife management, a deep respect for birds also comes from an appropriate appreciation of how they manage to survive and navigate the thousands of miles of diverse terrain and topography that they cover twice each year without using detailed maps, five-star hotels, or transportation systems, such as cars or airplanes.

Despite our appreciation and reverence for birds, scientists have discovered that over the last half-century, many species of North American migratory birds have declined substantially. One study concluded there are 3 billion fewer birds in North America today than in 1970, many of which are migratory passerines such as warblers, sparrows, thrushes, etc. One of those dramatically declining species is the Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), secretive woodland bird slightly smaller than a robin that sports a reddish-brown head, back, wings, and tail, and a white belly with exquisite black spotting on the breast and sides. The songs of breeding male Wood Thrush is a complex series of whistles and bubbly notes that somehow comes out in a very smooth, pleasant song.

In general, biologists know what habitats Wood Thrushes use throughout the calendar year, where they make nests in the forests, where they go to raise their recently hatched young, where they go during the winter, and what they eat. Using this information, biologists have sought to conserve this species throughout its known breeding and wintering ranges. However, in spite of these efforts, Wood Thrush is expressing substantial population declines, alongside many other North American bird species. We are coming to find out that our current knowledge is not enough to ensure this species continues to persist in our backyards and favorite hiking trails. Essentially, our current picture of what successful conservation looks like for Wood Thrushes is soberingly incomplete.

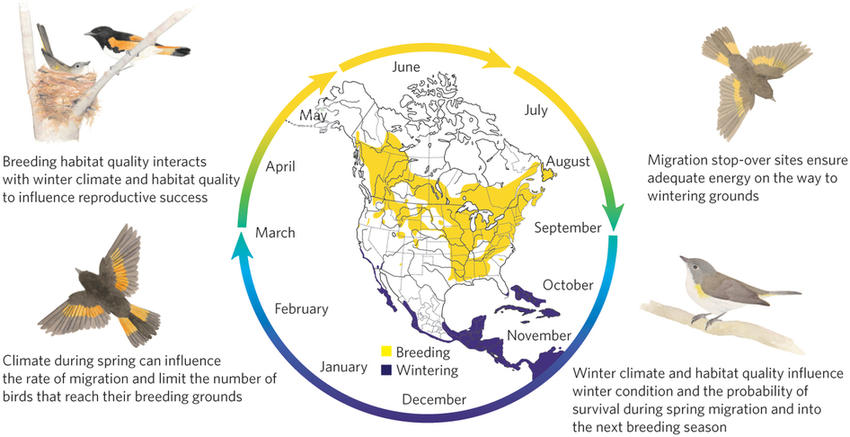

To provide a more complete understanding of this species and why it could be declining, Sarah Kendrick, a United States Fish and Wildlife biologist, initiated a Wood Thrush tracking project with the objective of deploying recently invented, small radio transmitters on as many Wood Thrushes as possible across the eastern U.S. and Canada from May through July 2024. The objective being to track the specific movements of individual Wood Thrushes, and their habitat use across the entire calendar year! To do so, biologists tagged the birds with radio transmitters and followed individual thrushes as they are detected by the radio tower network, namely the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, around the western hemisphere throughout the calendar year. By summers end, biologists from a multitude of conservation agencies and organizations tagged nearly 600 Wood Thrushes comprising individuals across the species’ breeding range in the eastern U.S. and Canada. This idea of measuring a bird’s movements and survival across then entire calendar year is known as “full annual cycle” research (see Figure 1). Full annual cycle research recognizes that Wood Thrushes are in different places of the world and doing different things depending on the time year and it is important to recognize that they all can influence Wood Thrush population sizes in different ways. Therefore, we should track their movements and how many survive during throughout the year to try and specifically pin point causes for their decline.

Figure 1. A graphic showing the different life stages of a bird across a full calendar year using American Redstarts (the illustrated bird) as an example. The same graphic applies to Wood Thrushes too! However, we are missing precise and specific information at many stages of the year for Wood Thrushes. We think tracking them throughout the year in specific ways will allow us to learn why Wood Thrushes are continuing to decline in spite of conservation efforts to prevent that.

Infographic credit: Small-Lorenz, Stacy & Culp, Leah & Ryder, Thomas & Will, Tom & Marra, Peter. (2013). A blind spot in climate change vulnerability assessments. Nature Climate Change. 3. 10.1038/nclimate1810.

Who is Involved in the Project?

Importantly, the Tennessee River Gorge provides habitat for a seemingly abundant breeding population of Wood Thrushes and for individual thrushes migrating through the area in the spring and autumn months. We deployed 10 radio transmitters on adult Wood Thrushes breeding specifically in the Tennessee River Gorge, hereafter Gorge, and then an additional tag on a thrush born just this year that we captured at our migration banding station. Our goal is to contribute to the broader project by researching a unique population and to serve our local goal of conserving Wood Thrushes in the Gorge.

However, the Wood Thrush motus tracking project is part of an international, collaborative Wood Thrush tracking project that seeks to increase our knowledge of this secretive songbird. Conservation organizations around the eastern U.S. and Canada have come together to accomplish tagging hundreds of Wood Thrushes and erecting hundreds of radio telemetry towers. This is no doubt a monumental effort that goes beyond our local conservation efforts. That being said, this project is built on local conservation efforts that collectively add to the whole. We at TRGT are one piece of the puzzle, but a necessary piece that spearheads conservation in the Gorge and surrounding areas. We thank our partners for the support and success of this project, namely, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. We also thank Laura Cook at Warner Parks who hosted an excellent bird capture and tagging training prior to tag deployment season.

Photos from the Field

Figures 2 through 4.

Figure 2 (top left). A biologist holds a captured Wood Thrush that will undergo a series of morphometric measurements and be fitted with a radio transmitter and banded using a numbered aluminum leg band.

Figure 3 (top right). A radio transmitter with two loops attached wherein the birds’ legs will sit in the loops so that the tag settles onto the back of the bird.

Figure 4 (bottom). A Wood Thrush in the dense understory habitat that they often use after breeding and during migration. This bird is sporting a radio transmitter that we attached.

You can follow our Tagged Wood Thrushes as they migrate!

As tagged birds move about the landscape and are detected by radio telemetry towers, each detection is displayed on the Motus website. Please visit this link to follow the movements of the Wood Thrushes tagged in Tennessee! The website that the link takes you too automatically creates a straight line connecting the towers that detect an individual Wood Thrush throughout its migratory movement. It’s important to recognize that the line is not necessarily the path that Wood Thrush took between towers, rather, it’s a simple visualization showing the minimum distance between the Motus towers.

Further REading

What is Motus?

Wildlife biologists have used radio telemetry since the late 1950’s and it entails attaching a very high frequency (VHF) radio transmitter to an animal and the biologist picks up that radio signal using a handheld receiver and antenna and proceeds to manually track the tagged creature. This works very well but is especially labor-intensive and becomes exceedingly difficult when more animals are tagged and if the animal is migratory. This is because the antenna/receiver must be in direct line of sight to the tagged animal, which requires a great deal of involvement by a trained professional to manually track the animal. This can work well for short periods of time on animals that cover relatively small areas. But this becomes impossible when considering a migrating bird, even if you have an air force at your disposal. So, to follow birds during migration scientists have used satellite transmitters, where a tag communicates with satellites to determine its position on the globe. Scientists have also used geolocator tags, where the tag records its position on the globe using day length and sunrise/sunset times.

Both of these wildlife tracking methods are excellent tools, but come at significant costs. Satellite tags are very expensive (thousands of dollars) and incur even more costs associated with annual fees for using satellite time. Furthermore, satellite tags are still impossible to use on many small wildlife. Even the smallest available satellite tags are still too large to fit on many species of migrant birds. Concerning geolocator tags, these tracking devices do not provide precise locations and cannot give specific migratory routes or the habitats used by the tagged animal. Geolocators and satellite tags also often require recapturing the individual animal in order to download the location data stored on the tag. This limits the researcher substantially in the amount of tags that can be reasonably deployed because recapturing individual birds is very difficult and labor intensive and simply not an option for many species.

Thankfully, however, through miniaturization and automation, it is now possible to make radio transmitters small enough to attach to all migrating bird species and to automatically track the radio transmitters via an automated receiver tower which can detect any tag within its range at any point during the day or night. These tags emit a very high frequency and can be small enough to fit on monarch butterflies and dragonflies! Another benefit to these tags, is that they cost hundreds of dollars, not thousands, and a single telemetry tower can cost less than one GPS tag and its associated satellite-use costs. It’s because of these advantages that scientists have built a global network of automated receiver towers, so they can easily track wildlife from their computer and track even the smallest of migrating birds over enormous distances as they migrate between where they nest and overwinter.

This network of towers is called the Motus Wildlife Tracking System. The word motus is Latin for “motion” or “movement”. Canada’s national bird conservation organization, i.e. Birds Canada, cleverly used this word to name their wildlife tracking system. The motus wildlife tracking system, hereafter motus, essentially uses the age-old VHF technology but in a new, innovative way. In the decade since the project’s birth in 2014, researchers, citizen scientists, and conservation organizations around the world have erected over 2,000 motus towers in 34 countries and collected tracking data on nearly 400 species of animals.

Tennessee River Gorge Trust staff erected a tower in 2023 in order to track the Wood Thrushes that we have tagged in 2024 and to contribute to other projects around the globe. In a little over a year, the tower has detected nearly 10 species of tagged birds. Including a very rare Kirtland’s Warbler! With each migration season, our tower and the thousands of others around the world provide greater insight into the hidden lives of migratory animals.

Something really great about motus is that anyone with internet access can see the movements of tagged animals online! You can go to www.motus.org and search any project or tower. If you visit this link, you can follow the movements of Tennessee Wood Thrushes tagged in the spring and summer of 2024.

Figure 5. A graphic from www.motus.org showing the concept of the Motus Wildlife Tracking System.

Figure 6. A motus tower from (https://motus.org/get-involved/host/) showing what a motus tower looks like. The antenna are on top that detect signals from the radio transmitters on wildlife. The solar panel provides power so that the antenna can work and upload the tags that they detect to the online database.