Louisiana Waterthrush and Worm-eating Warbler Geolocator Research

A large population of Louisiana Waterthrush (LOWA) and Worm-eating Warblers (WEWA) use the TN River Gorge to breed each summer. Since the LOWA relies on clean, healthy streams, while the WEWA relies on forested slopes with dense vegetation, their presence can tell us a lot about the health of our forests. The Tennessee River Gorge Trust has been researching these species and keeping an eye over the local population.

Louisiana Waterthrushes (LOWA; shown above) and Worm-eating Warblers (WEWA) are Neotropical songbirds that have been identified as a "species in decline" by the regional authority on bird population health, Appalachian Mountain Joint Venture. However, LOWA populations are on the rise within our specific region, making the Tennessee River Gorge an area of regional importance. LOWA serve as stream health indicators because they feed on macroinvertebrates such as mayfly larvae which are only found in healthy water sources while WEWA serve as an indicator specie of forest health. At the Trust, we want to understand what pressures are causing these birds to decline and the statuses of our own populations.

Cultural Background

We have combined a cultural component to this fascinating project alongside La Paz Chattanooga that aims to connect communities on each end of the birds’ migration. To learn more about this work with our Guatemalan partners, visit this link: https://www.trgt.org/guatemala

Scientific Background

There are many complexities involved in the conservation of migratory bird species. The sheer fact that they spend half of the year in two separate geographic regions, which can often be in multiple countries, can complicate conservation efforts and the acquisition of full life-cycle data. For example, a local population of a specific bird species in the Chattanooga area may be declining, but this could be solely due to factors on its wintering ground in Central America rather than anything occurring in Chattanooga (or vice-versa). In this case, sufficient conservation efforts would require knowledge regarding where the bird spends their time away from the breeding grounds and collaborative international action. New technological innovations like light-level geolocators are one of the means in which researchers can now obtain this imperative "full life-cycle data" and then properly inform conservation action. The Tennessee River Gorge Trust and its partners are taking advantage of this technology to answer questions regarding the simultaneous decline and increase of Worm-eating Warblers and Louisiana Waterthrush populations. This project is a collaborative study by the Tennessee River Gorge Trust, University of Toledo, University of Tennessee Chattanooga, University of Tennessee, and Harding University. The project was funded by the Lyndhurst Foundation and the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency.

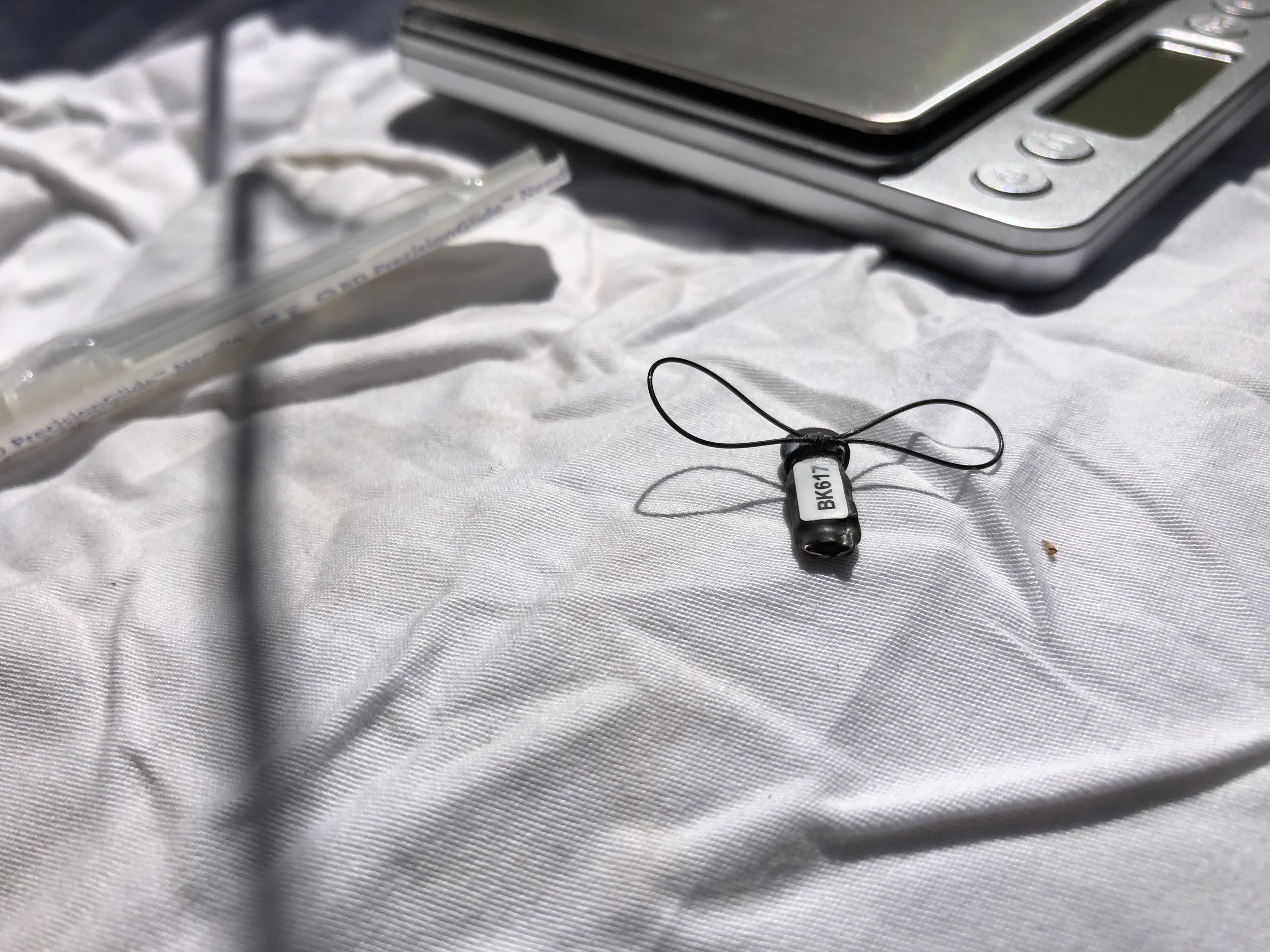

From left to right: Worm-eating Warbler, Eliot Berz and Holland Youngman attaching a geolocator on a Louisiana Waterthrush, and a Louisiana Waterthrush wearing a geolocator.

Project Overview

Figure 1. Study locations (gold stars) where individuals from the two species were marked with geolcoators. Arrow next to species abbreviations indicate increasing (blue up arrows) or decreasing (red down arrows) trends in abundance over the past 50 years. Insets in the upper left demonstrate the extensive overlap in breeding and non-breeding distributions for these species. (Figure from Dr. Henry Streby)

Louisiana Waterthrush and Worm-eating Warblers are two migratory bird species that present a unique research opportunity. These two species overlap extensively in their breeding distributions (eastern United States) and non-breeding distributions (Central America and the Caribbean) in addition to sharing similar breeding behaviors and habitat requirements. Despite their robust similarities, there are many locations across the United States where one has experienced local population increases over recent decades while the other has experienced substantial declines over the same period. For example, in the Tennessee River Gorge’s region, the Worm-eating Warbler has decreased in abundance by greater than 1.5% annually while Louisiana Waterthrush have increased by greater than 1.5% annually over the past 50 years. Conversely, in southeastern Pennsylvania and southern Ohio, the opposite trends have occurred for each species. A 1.5% annual decrease may seem like a small number at first glance, but consider the effect of this percent decline over the course of 50 years; it becomes a much more sobering number. Since one of these species is flourishing while the other is declining in the same areas over the same time period, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the problem may not be occurring here in the United States, but rather on differing wintering grounds in Central American and the Caribbean. Our research collaborators have hypothesized that the locally opposing population trends are associated with differences in the location where each population is spending its winter and the migration routes to get there. Habitat degradation may be occurring at the wintering sites of the declining populations while the increasing populations are not facing such constraints at their respective wintering sites. The research objective is to investigate this issue by tracking the migration of the two species over 4 separate geographic areas with light-level geolocator devices (Migrate Technologies Intigeo-W55Z9-DIPv9) and DNA samples in order to learn where the locally declining and increasing populations are spending their winters.

What is a geolocator?

Thanks to the miniaturization of tracking devices, we are beginning to learn about the migratory behaviors of previously enigmatic species. The particular tracking device that TRGT and our partners used is called a light-level geolocator. These geolocators record ambient sunlight levels in reference to time in order to determine its location on Earth.

A tricky component of these geolocators is that they do not transmit any signal back to the researchers, but rather store the data until the device is returned. This means that researchers have to recapture specific birds after they have migrated over 1,000 miles each way and spent half of the year in a distant country. Despite this obstacle, many bird species will often return to the exact same territory to breed year after year. Therefore, researchers can equip devices to individual birds and send them on their way, only to recapture the exact same bird in the same spot the following year.

This is an exciting time in the avian research world. With modern technological advances, researchers are able to attach smaller and smaller tracking devices on migratory birds. Incredible innovations have led to the creation of tracking units as small as a half of a gram (roughly the weight of a paperclip)! These innovations have allowed researchers to now safely track all but the smallest bird species.

2016-17 Pilot Study

In the summer of 2016, the TRGT bird research team deployed geolocator data loggers on sixteen adult male Louisiana Waterthrush as a pilot project to learn more about their full life cycle. These geolocators map the birds’ migratory routes and wintering grounds by measuring ambient light levels in association with time of day. These data can only be retrieved directly from the geolocators; thus, the researchers had to recapture the geolocator-carrying birds upon their return to the Gorge in the summer of 2017. Since thes songbirds often return to the same summer breeding grounds year after year, the researchers are able to successfully and safely recapture individuals as they return from their southern wintering grounds. Over the summer of 2017, five of the geolocator carrying birds were recaptured tracking units intact. The data revealed that the watherthrushes migrated to various locations within Guatemala and Southern Mexico, a round trip of over 3,000 miles! This project has been one of the first successful attempts at tracking the migration routes of the Louisiana Waterthrush. This field research project demonstrated that geolocator devices can be safely attached to these small, migratory songbirds and supported the approval by the federal regulatory body, the USGS Bird Banding Laboratory, to mark larger sample sizes of the species in future research.

2018 Multi-state Project

After receiving funding from the Lyndhurst Foundation and the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, TRGT moved forward with the purchase of 120 geolocator units from Migrate Technologies. A total of 120 male birds (60 of each species) were successfully tagged with geolocators (15 LOWA and 15 WEWA at each site) by TRGT Avian Technicians, Dr. Henry Streby’s lab at the University of Toledo, and Dr. Patrick Ruhl at Harding University. Equivalent numbers of male individuals were marked with only leg bands at each site to serve as a control group. We used observational parameters such as paring with a female, building of nest, and time of year before capture efforts were made to ensure that each bird was going to breed and remain at the study sites. All birds were captured using mist nets, audio playbacks, and decoys. Upon capture, each individual was marked with a plastic color leg band and federally issued metal leg band. Blood cell and plasma samples were placed in separate storage tubes, flash frozen in the field, and transported to the lab for later analysis of DNA: telomere length (an index of stress and age) and immune response (testing the strength of the immune system). We will complete an exhaustive search for returning birds at each site from March-June of 2019 to find out where the bird migrated!

2019 Multi-state Project

After much hard work, TRGT recaptured 12 migratory birds wearing geolocator tracking devices! This makes a total of 39 returned geolocators for the overall study with our partners at the University of Toledo, University of Tennessee Chattanooga, and Harding University. An additional 29 birds were recaptured as control birds wearing only leg bands. The research team is currently analyzing the data to uncover where the recaptured birds traveled to over the winter, so stay tuned for the exciting results! TRGT discovered exciting results from a preliminary pilot study tracking Waterthrush migration back in 2016 and 2017. The geolocators revealed an astonishingly fast migration speed (an average of 7 days for a journey of over 1,000 miles)! We are eager to uncover what information these new 39 geolocators are holding.

These birds were equipped with geolocators in the summer of 2018, then flew 1,000+ miles to spend their winter in the tropics. This was the first time Worm-eating Warbler migration has been tracked and one of the initial studies for Louisiana Waterthrush migration.

2020 Tennessee Project

In 2020, 16 additional geolocators were attached to 8 adult Worm-eating Warblers and 8 Louisiana Waterthrush in the Tennessee River Gorge. This addition to the study was funded by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency to obtain more data to connect Tennessee’s local populations of breeding migratory songbirds with their respective wintering grounds.

2021 Tennessee Project

In 2021, the TRGT bird research team recovered 3 geolocators from Louisiana Waterthrush and 4 from Worm-eating Warblers upon their return to breeding territories within the Gorge. Stay tuned for detailed information about the bird’s journeys.

This project was funded by the Lyndhurst Foundation and the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency.

The final count for the 2018 bird banding season is here!