Using bird migration to establish connections between international communities.

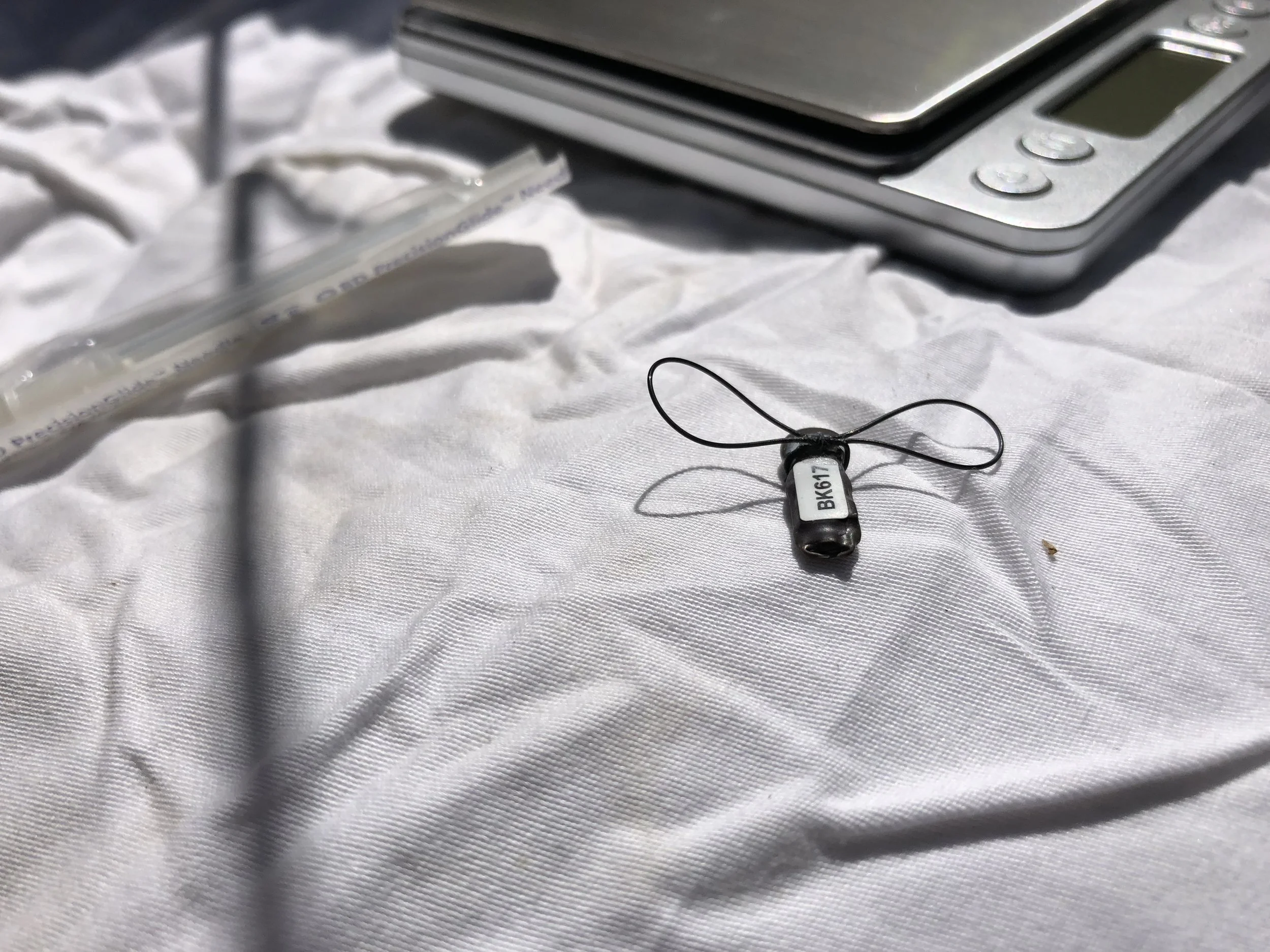

TRGT, University of Toledo, Harding University, and the University of Tennessee Chattanooga have successfully deployed 120 geolocator tracking units on 120 migratory birds in order to investigate the concerning population trends between the two species.

It was a brisk, March morning when Mariah and I made our way to Mill Creek. Our wool hats pulled tight and our dip nets and buckets in tow, we picked our way down alongside a series of splashy, miniature waterfalls. In contrast to the solemn gray river, cutting through the gorge below, the flowing tributary appeared especially bright and lively.

A recap of the 2017 bird banding season in the Tennessee River Gorge.

We huffed our way up the tight, rocky path, climbing over wind-toppled trees and stumbling over rocks. Far below, I could see the sun-bleached Tennessee River. In fact, I could almost hear it – even over the crunch of dry leaves – a churning, static noise that seemed to be getting louder.

On the north sides of the buildings snow persists from the weekend dusting, a fragile sheet of ice covers the pond, and the sun still lingers low as we pass by. The tilt is shifting, though, and these days of crisp, cool, clarity are numbered.

It’s a crisp fall morning. The cool air reaches your lungs as each footstep carries you over a complex rock garden, covered in slippery moss. You break through spider webs, and your legs and lungs feel every ounce of effort needed to propel your body up the next hill. Eyes glued to the trail, looking for roots or rocks that might trip you up, you find your rhythm.

There are many relationships that stitch together the tapestry of a place as biodiverse as the Tennessee River Gorge. John Muir famously wrote that “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” Some of those relationships are distant, tertiary. Others are direct and dependent, like the one between a striking butterfly and its’ host tree that are native to the Gorge.

We went by boot, snake gaiters strapped to our shins. Alongside the narrow canyon road, there was no beaten path so Executive Director Rick Huffines and I climbed through honeysuckle then started up a shallow creek, scrambling over mossy boulders.

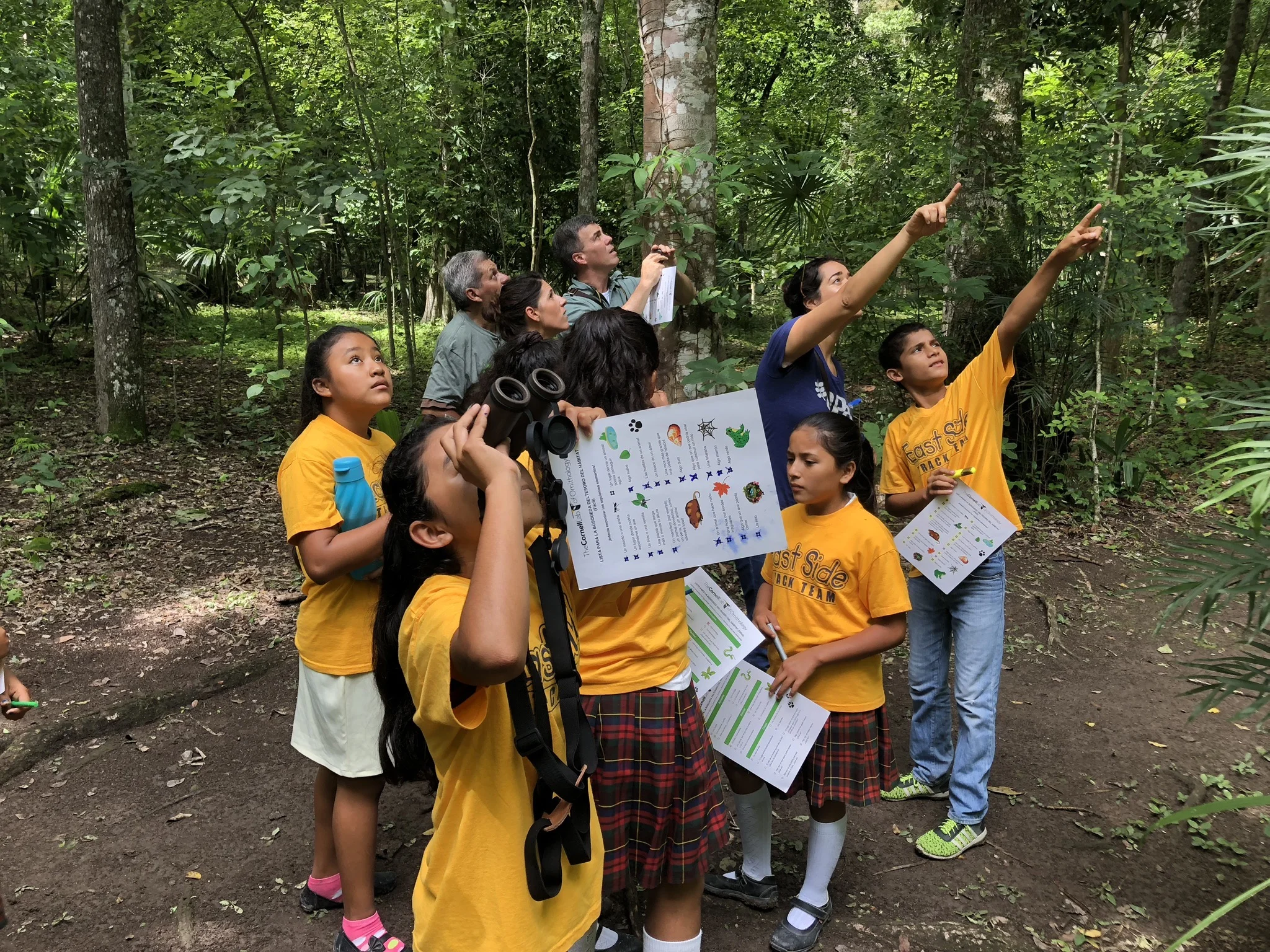

Partnerships in nature come in all shapes and sizes, and rely on each other for survival—and to support entire ecosystems. We can find analogies throughout nature that represent the partnerships we’ve established that support the work we do here at the Trust.

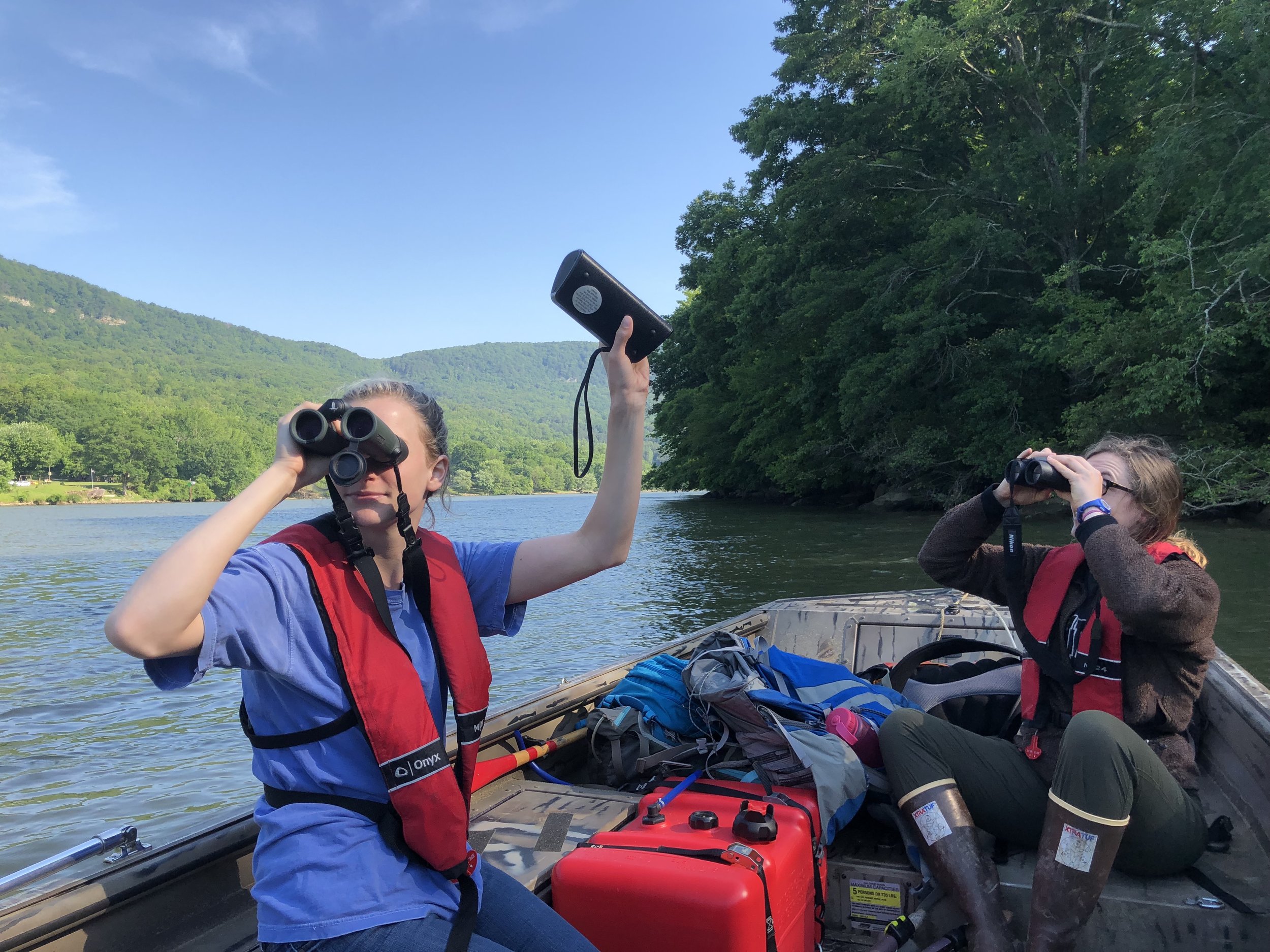

The question was posed to me by Rick Huffines early one spring morning. The sun had just crested Signal Mountain, spilling orange into half the river gorge while the other half remained dusky-blue. It was cooler on the water than I had planned for. I hunched my shoulders against the wind as Rick and I bumped against the current in his motorboat.

We sometimes forget we are natural creatures with natural rhythms. As a society, we've outsmarted even ourselves, creating tools and means to work faster and harder and more. Just generally MORE.

And yet, all of this progress stands in the face a fact we like to ignore: we are limited, natural beings.

The Trust has three research projects running simultaneously: our Worm-eating Warbler Survey, our Long-Term Bird Monitoring and Inventory Program, and our Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. Meet the crew conducting this awesome research.

At the Trust, we don't think of our work as sexy: We aren’t developing the latest iPhone apps. We can’t give you tasting notes on local craft beers. And we definitely aren’t touting ways to trim that stubborn belly fat with PiYo.

Our work isn't trendy. And that’s okay by us.

Nature, like what we have in the Tennessee River Gorge, offers us that “ultimate meaning” that we are seeking. In becoming attuned to our connection to the “remainder of life,” in the form of trees, springs, birds, and wildflowers, we can be reminded of and comforted by our place in this world.

“So, what do you guys do?”

That’s the question I hear most often after introducing myself as the Business & Creative Director at the Trust. It's a fair question, and to answer I’d like to give you a rundown of our duties.

In honor of the new year, we have prepared a list of (20)14 reasons to love the Tennessee River Gorge.

This bird is the first domino.

The Cerulean Warbler’s health (or lack thereof) directly indicates the health of our surroundings. It’s not about the bird. It’s not about the trees. It’s not about nature for nature’s sake.

As I was sitting in the chaos, a thought began to form: Why am I here? Why did I take this job? Why do I do the conservation work that I do? Those pieces of paper held passion. Vision. A people moved. What was my reason?